For three decades, the two artists who first met in Zürich in 1915 and later married in 1922, enjoyed a fruitful, intense, artistic relationship marked by several joint projects. Taeuber was 26 when she first crossed paths with Jean/Hans Arp. A graduate of the interdisciplinary Debschitz School in Munich, the artist taught textile design at the Kunstgewerbeschule (school of arts and crafts) in Zurich. She visited the exhibition Modern Tapestries, Embroideries, Paintings and Drawings at the Galerie Tanner, where Arp was presenting pieces alongside Otto van Rees and Adya van Rees-Dutilh. Shortly after, presumably in the spring of 1917, Taeuber and Arp fell in love.

By then, Zürich had become a hothouse for freethinking, rebellious spirits and gave birth to a new movement, Dadaism, which sought to banish bourgeois culture in style. In February 1916, a group of exiled artists gathered and took a pledge in a café tucked away in a backstreet of the old town, the mythical Cabaret Voltaire. These young people denounced beauty, sentimental poets and, most importantly, the war sweeping Europe at the turn of the century.

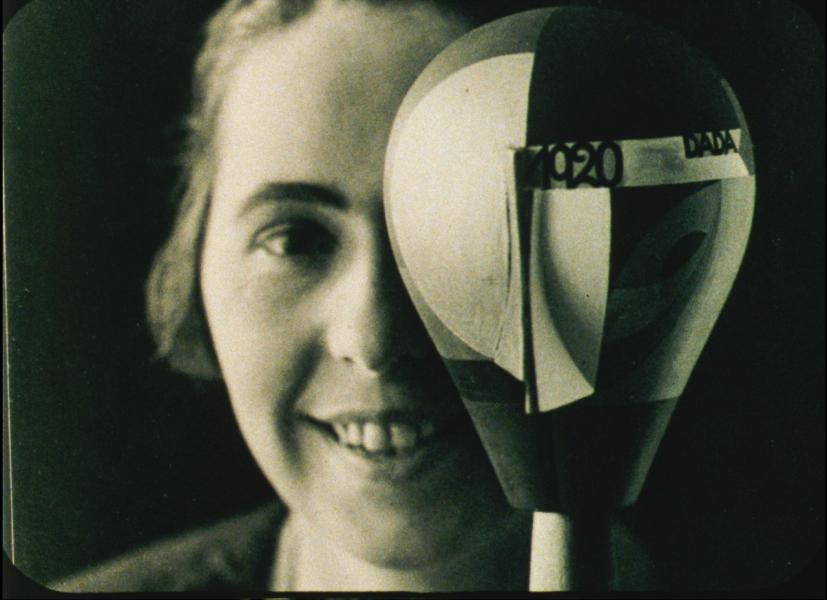

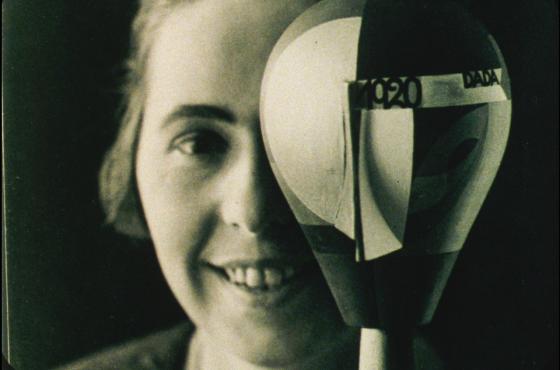

Sophie Taeuber also challenged established art forms. Her 1916 encounter with Arp drew her into the circle of the Dadaists and she eagerly took part in their activities. Having danced since 1915 and been in contact with the great Rudolf von Laban, a prominent dance figure and the founder of European Modern Dance, she executed expressive dances to mark the opening of the Galerie Dada in 1917.

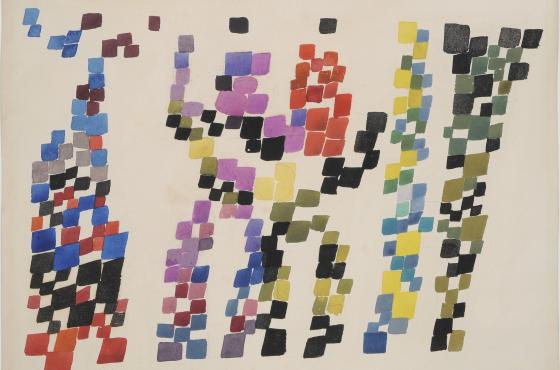

In 1948, Jean Arp reminisced about this period and meeting ‘his’ Sophie: “In December 1915, I met Sophie Taeuber in Zurich. She had freed herself of conventional art. She showed me drawings, tapestries and embroideries that were exclusively made up of vertical and horizontal lines.” Between 1918 and 1920, the couple produced five large collages. Entitled Duo-Collages, these pieces incarnate Concrete Art. Built around the concept of rectangular shapes, the collages foreshadowed Minimalist Art.

They were probably the first manifestations of their kind. Pictures that were their own reality, without meaning or cerebral intention. We rejected everything in the nature of a copy or a description, in order to give free flow to what was elemental and spontaneous.

A joint masterpiece

The structure and colours of the Duo-Collages also served as a template for the stained-glass window in the stairwell of the Aubette, one of their largest joint works. A listed monument today, it forms part of the museums of the city of Strasbourg under the name Aubette 1928.

In the late 1920s, Sophie Taeuber was commissioned by brothers Paul and André Horn to redecorate the vast building. To design the space destined to become a leisure centre, she enlisted the help of Jean Arp and Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch painter, architect, and art theorist well known as the founder of the De Stijl movement. Together, the three artists designed a dozen rooms spanning four floors in the spirit of a Gesamtkunstwerk.

While some of these spaces were created collaboratively, others were made individually by each artist. However, Theo van Doesburg reaped the rewards of the project by failing to credit Taeuber and Arp in the magazine De Stijl dedicated to the Aubette. There was hardly any mention of Jean Arp in the magazine, and he only cited Sophie Taeuber’s “good taste”, thereby minimising her role as project manager.

This characterisation of the Swiss artist’s work echoes Linda Nochlin’s ground-breaking 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? - published by ARTnews. In it, Nochlin dismantles the notion of artistic genius codified by men, exposing the institutional structures that contributed – to a large extent – to render women invisible and that eclipsed the importance of networks in the careers of artists.

In 1943, following the tragic death of Sophie Taeuber, who was asphyxiated by emanations from a coal stove at Max Bill’s Zurich home, on the eve of an impending return to France, Jean Arp sank into a severe depression at a time when his physical and mental health was already wavering due to the Second World War. Although the grieving husband had the best intentions, he was instrumental in immortalising Sophie’s image in admittedly poignant texts, which nevertheless tended “to imprison her in a somewhat indeterminate realm, somewhere between elegy, dream, and reality,” as art historian Cécile Bargues described it.

Bruised and heartbroken, Arp penned these lines one year after his wife’s death:

You would always dream of winged stars,

of flowers cajoling flowers

on the lips of infinity

You dreamed of things that rest in the immutable home of light

You painted an unveiled rose

A bouquet of waves

A living crystal

Distraught, Jean Arp and his friends Michel Seuphor, Marcel Janco and Hans Richter gathered together to cherish the memory of Sophie, who was transformed into a sacrificial angel. They talked a lot about her, mostly in her name.

Sophie under a new light

According to art historian Isabelle Ewig, the first Sophie Taeuber-Arp exhibition at Bozar – curated by Jean Arp and Hugo Weber in 1948 – was intended to cement her reputation as a painter and sculptor by completing unfinished pieces or by producing new versions of Taeuber’s original projects. Walburga Krupp, commissioner of the exhibition, demonstrated in her research that Arp referred to several collages as duo works, although they had probably not been produced together at the time. Moreover, the catalogue made no mention of Taeuber’s other activities, such as her marionettes (puppets), stage sets, murals and interior designs, including the Aubette.

There was also no mention of the fact that, between 1925 and 1942, Sophie Taeuber participated in some forty exhibitions in major museums in Europe, the United States and Japan. Her private archives have thus become valuable sources for historians. Indeed, it is precisely this insight into the intimate sphere of her life that allows us to see Sophie Taeuber under a new light. For she was not at all a sacrificial angel, forever smiling and spontaneous.

In 2021, the publication of several hitherto unpublished letters written by Sophie Taeuber-Arp to her husband Jean, her sister and other friends shed new light on her life. Compiled in three imposing volumes edited by Medea Hoch, Walburga Krupp, and Sigrid Schade, the collection features 431 letters and postcards, dating from 1905 to December 1942, shortly before her death.

The book indicates that Arp helped Taeuber grasp the importance of her pioneering artistic achievements. But, on the other hand, Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s artistic career suffered from the competition with her husband. Taeuber often handled Arp’s preliminary drawings and finished his pieces so he could complete commissions. After that, she had to focus on her personal artistic work and the many domestic and administrative chores he could not be bothered with.

We should also (re-)examine the history of the Aubette, nicknamed the ‘Sistine Chapel of abstract art’, which was envisioned without distinction between the fine arts, decorative arts and interior architecture. The artist who had chosen to remain publicly silent regarding Van Doesburg’s comments in the 1928 edition of the De Stijl magazine opens up about the affair in a letter to Louise Maass, one of her former classmates at the Debschitz School: “I have tried hard to understand Van Doesburg’s theories. He claims his compositions have nothing to do with decoration at all, that they are purely spatial. Some are very beautiful, but I think he is making up a theory to please himself. I notice how Van Doesburg falls afoul of everyone because he overestimates himself to such an extent that he always feels misunderstood and abused.”

Another letter bares her wrath:

He used his work as a journalist to promote the Aubette as his own, leaving out our names. I am gradually beginning to lose my patience, especially since the commission was awarded to us and we only engaged Van Doesburg because it was too much work on top of our other activities.

Like Sophie Taeuber, other female artists were instrumental in introducing paradigm shifts that have led to a historically unprecedented valorisation of so-called minor arts. These women could seamlessly switch from one discipline to another, which was perhaps indicative of the multiple roles they fulfilled as women in their era, as female artists, and as artists’ wives. All of these roles reinforce the idea that, from their perspective, these disciplines were non-hierarchical and were part of the fabric of their everyday lives.

The exhibition Hans/Jean Arp & Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Friends, Lovers, Partners runs from 20 September to 19 January.