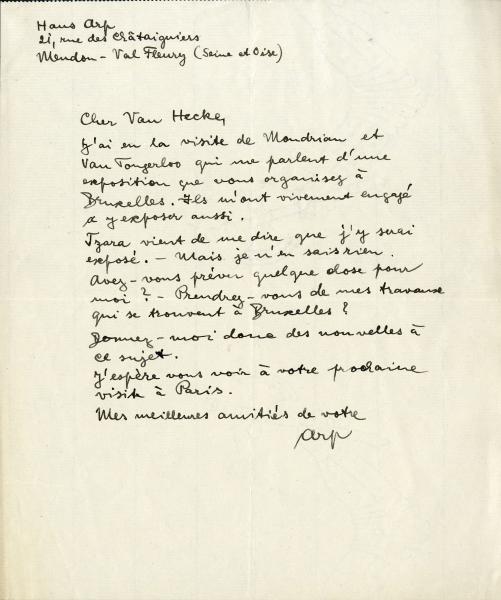

Look at this! I’ve found a handwritten letter from Arp – first name omitted – in the archives of the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Undated, but it must be from early 1931. Hans Arp wrote it from 21 Rue des Châtaigniers, in southwest Paris. In a rectangular house with a garden designed by his wife Sophie Taeuber, where the couple had lived and worked together since 1929. Sophie’s studio was on the third floor, from where she looked out over the Parisian suburbs and ran their entire business. Life and art were indivisible. (Coincidentally, the artists’ house has survived intact. It is now home to the Arp Foundation, who keep the memory of the Dada couple alive.)

Hans’ letter is addressed to one Van Hecke – again, no first name. This is Paul-Gustave, or Pégé, Gust or Tatave to his friends. He was the man behind the Brussels galleries Sélection and L’Époque, but who switched to fashion with his wife Norine in the late 1920s. However, the couturier-art dealer still worked for the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1931 - home of the non-profit association L’art vivant [Living Art]. The organisation wanted to provide a lifeline for artists after the stock market crash, which had sent the prices of their work plummeting.

Pégé mounted the large-scale exhibition L’art vivant en Europe [Living Art in Europe] at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, an almost unprecedented survey of post-Impressionist art movements, in which artists were only too happy to participate. The overview was structured by country: France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Czechoslovakia. A large room was also reserved for the ‘school of Paris’, on the grounds that numerous artistic innovators from the surrounding countries had ended up in the City of Light after the First World War.

DADADA

The ‘art vivant’ archive box contains a clutch of letters to Van Hecke from the pioneers of modern art: Arp, Kurt Schwitters, Piet Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, René Magritte, .... In his letter, Arp tells Pégé that Mondrian and Vantongerloo, two early pacesetters of the De Stijl movement, had visited him at Rue des Châtaigniers. They had urged him to participate in L’art vivant en Europe. Hans, that is, not his wife Sophie.

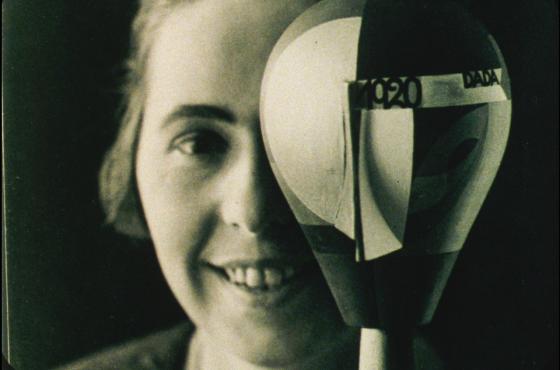

After Mondrian and Vantongerloo parted company with the Arps, Tristan Tzara came knocking on their door. Tzara, Arp and Taeuber had known each other for a long time – since the days of the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. This was the nightclub in neutral Switzerland, in which Dada had been boisterously christened in 1916. Dadaism gave a mighty finger to the violent, individualist and nationalist slant of the First World War. Art forms tumbled merrily over each other. Egos ran amok. Hans recited his sound-rich poems at the Cabaret. Sophie turned heads with an expressionist dance in a cubist-futuristic outfit. Romanian Tristan Tzara egged the entire creative circus onwards: ‘Da, da!’ (Yes, yes!)

Now, what Tzara had to say to the Arps was this: Hans’ work would be shown in L’art vivant en Europe anyway. Or so he’d been told by his friend E.L.T. Mesens, the poet, collagist, artist, jack-of-all-trades and ‘sales secretary’ to the exhibition. “Are you including works of mine that are in Brussels?”, Arp asks Van Hecke. “Let me know!”

Pégé and E.L.T. Mesens had effectively selected La planche à oeufs [Egg Board], a large relief from the collection of Paul-Gustave van Hecke and Norine, and Oiseaux [Birds] from the collection of Pierre Janlet, one of the driving forces behind the Palais des Beaux-Arts. As an aside: the first work was auctioned two years later for a rock-bottom price, along with the rest of the Van Hecke collection, including dozens of Magrittes. The second fetched the hammer price of 3.5 million euros at Sotheby’s in 2022. Things certainly change in the art market.

À L'Époque

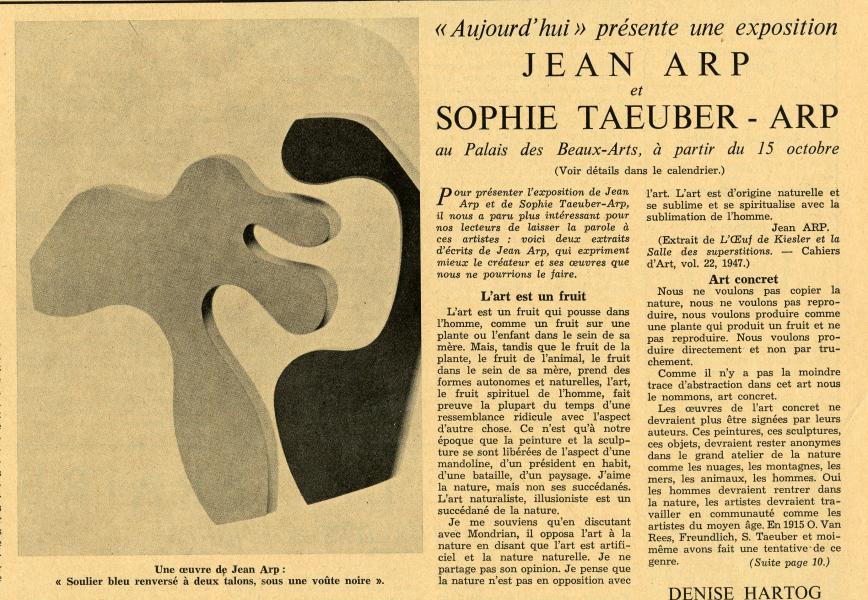

Hans Arp gives a disarming, childlike twist to the everyday in his wooden reliefs. They resemble magnified pieces of scenery from a Surrealist school play. Birds and eggs. Bottles and vases. Fragments of people: lips, noses, moustaches, navels. Plastrons.

Oiseaux, also called L’O et L’U de l’oiseau, dates from 1928. In May of that year, Hans and Sophie had travelled to Brussels for the opening of Arp’s solo exhibition at L’Époque gallery. Sophie wrote a postcard to her sister Erika on 14 May 1928: Arp has painted two large reliefs in Brussels, and she is going to try on dresses. It is extremely likely, therefore, that Oiseaux was created in the Belgian capital and immediately sold.

The Arp exhibition at L’Époque was captured for posterity by a photographer: several installations shots survive, as well as pictures of five besuited gentlemen. In the centre: Joan Miró, with a cane, and Arp. Around them: three ostentatious poet-artists. Alongside Van Hecke and E.L.T. Mesens, we discern Camille Goemans, one of the pioneers of Surrealism in Brussels and a close friend of Magritte. Arp had signed an exclusive contract with Goemans in 1927.

Both Magritte and Goemans moved to Paris that year, where they regularly dined with Arp, Miró and Dalí. In May 1929, Goemans opened a gallery at 49 Rue de Seine and hired Sophie Taeuber to oversee its interior design. The first exhibition at Galerie Goemans was dedicated to her husband.

And Sophie ?

Yet Sophie Taeuber-Arp had long been the artist couple’s regular breadwinner. She taught at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts but also made artworks for Hans. For example, she attached the cords that formed the contours of faces in unbroken lines. Georgette Magritte completed the job when Sophie was in Zurich.

But E.L.T. Mesens and Paul-Gustave van Hecke, the director and owner of L’Époque respectively, set their sights firmly on Hans Arp in 1928. His solo exhibition opened at their gallery on Saturday 5 May – the day after King Albert had officially inaugurated the Palais des Beaux-Arts. I stare at the photos of the opening and imagine that Sophie and Hans were also present, there, in that jam-packed sculpture hall. It was the art event of the year for Brussels.

The twenty-nine-year-old owner of Oiseaux, Pierre Janlet, was then the right-hand man of Henry Le Boeuf, the driving force behind the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Janlet would later become its General Director. He amassed a superb art collection during his career and also struck gold at L’Époque in 1928. He purchased Arp’s Lèvres écossaises [Scottish Lips], amongst other pieces. The relief hung in the gallery’s right-hand room, to the left of the fireplace. On the other side: La planche à oeufs. Ninety-six years later, the two reliefs will be reunited in Bozar. They are coming home – to Brussels.

The exhibition Hans/Jean Arp & Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Friends, Lovers, Partners runs from 20 September 2024 to 19 January 2025.