The title came right at the end: Khorós. The word not only alludes to polyphonic singing, but also to the chorus that sings and dances together in Greek tragedies. The folk dances have regional variations that can all be traced back to the same basic themes and motifs. This is also true of De Bruyckere’s oeuvre. Horse bodies, weather-beaten blankets and animal skins, trees, flowers, headless corpses, phalluses and vulvas all recur in changing constellations. They deepen meaning. De Bruyckere’s images occupy a liminal realm, a form that is between man and animal, tree and man, genital and flower.. Identity remains a malleable and evolving concept.

Images that resonate

Khorós is Berlinde De Bruyckere’s first major solo show in Brussels. It is also the inaugural event in a new series at Bozar. Director Zoë Gray has given it the title Conversation Pieces. Artists are invited to enter into a dialogue with their own work, as well as that of others. De Bruyckere sees this as an opportunity to reflect on sculptures from the past quarter-century and the conversations she has had with artists from various disciplines and eras. ‘Working in dialogue is my favourite method,’ she explains during a presentation for Bozar staff. ‘Relating to people, sensible of what is going on around me. I didn’t want a traditional retrospective, but why not examine the dialogues I’ve had? Who has shaped my work? Who helped me develop my unique world and vocabulary?’

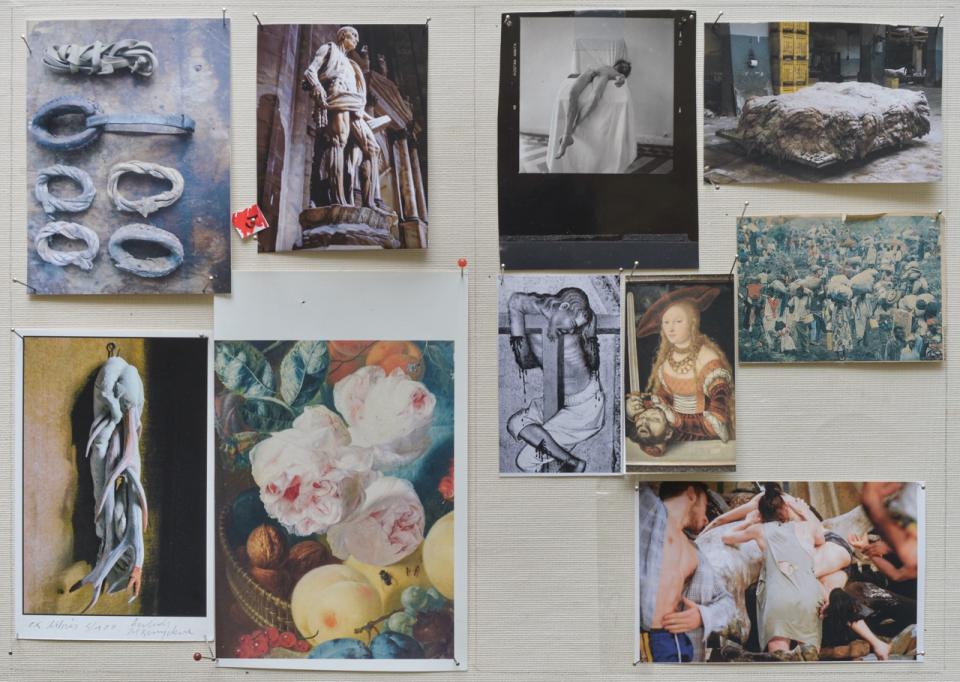

The Italian film-maker Pier Paolo Pasolini is the first to help set the tone. In her studio, she begins to assemble stills from different films. ‘Which images touch me? How can I also foster a dialogue between the photos?’ De Bruyckere seems predominantly focused on the actors’ poses and physicality. Naked bodies that touch each other. Limbs that reach out and unfold. Damaged corpses lying on the ground.

Not everything runs in perfect synchrony in Khorós. In one of the final rooms, for example, you encounter Into One-Another. To P.P.P. A tangled body lies in an old, repurposed museum display case. Since they have no head, they have no eyes with which to exchange an understanding glance. And yet you feel compassion for all that carnality, for the blue-veined and red-bruised waxy skin. There is no P.P.P, no Pier Paolo Pasolini, to be seen in this room. However, there is another of De Bruyckere’s sparring partners, the Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach the Elder. One of his works depicts Salome offering up John the Baptist’s decapitated head on a platter.

Beginning/End

As well as death, there is also a striking degree of eroticism in Khorós. It has become increasingly prominent in De Bruyckere’s work over the past few years. She herself acknowledges that her works have not fully explored the theme of sexuality, leading some to speculate whether it was due to shyness. In one of her most recent conversations, she explored the contrast between the Hindu symbols of Lingam and Yoni, representing Shiva as a phallus emerging from a vulva. During a trip to India, De Bruyckere observed a fertility ritual where milk was poured over the Lingam and Yoni, adorned with flowers. This led her to contemplate her own drawings of floral forms that could be interpreted as either genitalia or flower petals.

‘I have the feeling that, through my work, I am continuing something else,’ De Bruyckere concludes. In the final room, she displays the earliest sculpture in the exhibition: Fran Dics (2001), a naked woman, made of wax, hiding in the foreground behind her abundant hair. This only enhances her vulnerability. Adjacent to this piece, De Bruyckere displays a recent series of collages, directly from the studio. The poet T.S. Eliot already knew it: ‘in my beginning is my end’. But also: ‘in my end is my beginning.’

Berlinde De Bruyckere. Khorós runs from 21 February until 31 August 2025