Few would guess that the wooden fence of two modest terraced houses in Ghent conceals the anything but modest offices of Robbrecht & Daem Architecten. The neighbourhood is perhaps even less of a giveaway, since the Brugse Poort is not exactly known for its pioneering architecture.

“It is a real working-class neighbourhood,” Paul Robbrecht candidly admits, “where people of different origins live together peacefully. Although I should immediately add that we purchased this immense plot before the prices started to shoot up here as well. It’s unbelievable what people pay here these days for a small house with little more than a door and a window. We’ve been extremely lucky.”

Formerly the site of a match factory, today some thirty-five people work in the architectural firm that Paul Robbrecht and his wife Hilde Daem launched in 1975. Among them is their son and professional partner Johannes Robbrecht, who naturally also got involved in Bozar’s request to add a new dimension to the concert experience this season. "We are a real family business," says Paul Robbrecht.

“Collegium Vocale and, especially, its founder Philippe Herreweghe have been incredibly important in my musical education."

And just how musical is that family?

Paul: “Not! We’re completely unmusical. We can’t read notes or even sing. Or wait, when I’m in the mood, I dare to venture into Irish ballads. (laughs) But we’re great music lovers.”

Johannes: “It was also instilled in me from an early age. As a nine-year-old, I was taken to Collegium Vocale concerts, where I sat in the front row listening to Bach’s St Matthew Passion.”

Did you enjoy that?

Johannes: “I loved it! Although at that age, it was also an endurance test.”

Paul: “I still find it an endurance test at my age! (laughs) But Collegium Vocale and, especially, its founder Philippe Herreweghe have been incredibly important in my musical education. We met in our twenties and often travelled to Italy together. I taught him about Renaissance architecture, he taught me about Renaissance music. That was an enormously rich exchange.”

One of your most famous designs is, of course, Concertgebouw Brugge. Did your love of music help you win that architectural competition?

Paul: “It’s quite possible. Gerard Mortier was on the jury and, by his own admission, he was a huge fan of our design. We’d also included a chamber music hall, even though it hadn’t been requested. But we said: you have to do it! And lo and behold, the hall is in constant use nowadays for string quartets and piano recitals. The dialogue you create between musicians in that kind of space is quite extraordinary. Meanwhile, many of the musicians who’ve played there have since become friends. Isabelle Faust, for example.”

We’ve mostly been discussing classical music. You’re less keen on pop, rock or jazz?

Paul: “I do like it, in fact. I was drawn into jazz by saxophonist Michel Mast. He plays with the Laughing Bastards nowadays, amongst others, but we once set up a little agency together, because he’s also an architect. We called it Architectuur en Muziek [Architecture and Music], and I still have some of the stationery lying around somewhere. (laughs) It was at an Archie Shepp concert, organised by Michel, when I first thought that jazz has something deep to it, after all. But you also listen to avant-garde pop don’t you, Johannes? Sonic Youth and all that.”

Johannes: “That’s not pop.”

Paul: “Well, then: noise.”

The reason I ask is because ‘staging the concert’ reminds me of those impressive stages that U2 take on their world tours.

Johannes: “I took my dad to Pukkelpop once, and to Radiohead and Björk at Rock Werchter.”

Paul: “I thought it was fantastic!”

Johannes: “But we’re not familiar with that kind of architecture. Besides, that wasn’t Bozar’s request either, to build a stage.”

Paul: “We were asked to converse with a piece of music from the perspective of our discipline. Because music is a language, as is architecture, of course. And so, we set geometry, the basis of architecture, against the structure of Béla Bartók’s Music for strings, percussion and celesta.”

Johannes: “Because we believe that we work in a similar way. How Bartók structured his work is not unlike how we, as architects, make space. Or at least, this is what we hope to demonstrate, that for us, music is architecture in time.”

That sounds ...

Paul: “Abstract? Absolutely! It’s got to remain a surprise.”

Johannes: “I can already reveal that the hall will contain two things: Bartók’s music and our intervention. And the aim is for them to maintain an equilibrium. You will also sense that both the percussive and ephemeral nature of the music form part of our intervention.”

Paul: “Moreover, we’re playing with Bartók’s instructions to divide the orchestra for this piece into two groups, between which there is a celesta – an unusual kind of piano.”

“Reflecting on music also made us look at our drawings differently."

So Bartók also worked architecturally?

Johannes: “Yes, in an extremely spatial way. But it’s not just within the performance, it’s also part of how the music is constructed. It will all become clear, very soon, in the Henry Le Bœuf Hall.”

What do you think of the rest of the Bozar building, by the way?

Paul: “By Victor Horta? Genius, of course.”

Johannes: “We’ve worked here before. We built the Cinematek, the Bozar café Victor is ours, and we’ve also designed a couple of exhibitions.”

Paul: “That interweaving of different art forms in one building, that Wagnerian idea of a gesamtkunstwerk extended to architecture, that’s the true strength of Horta’s achievement. But what I find most fascinating about the building, perhaps, is that it’s barely a wall high on the Royal Palace side, whereas on the other, it is itself a real palace.”

Was Staging the Concert a challenge or was it mostly fun?

Johannes: (straightens up) “We flew with it! The challenge, if any, lay in the fact that it had to be realised to a tight deadline, but that’s what made it so fun. Things often move very slowly in architecture. We have projects that take fifteen to twenty years to complete, like the Book Tower in Ghent. Taking something like Staging the Concert in between these jobs, and pulling it together in under a year, that really energises you.”

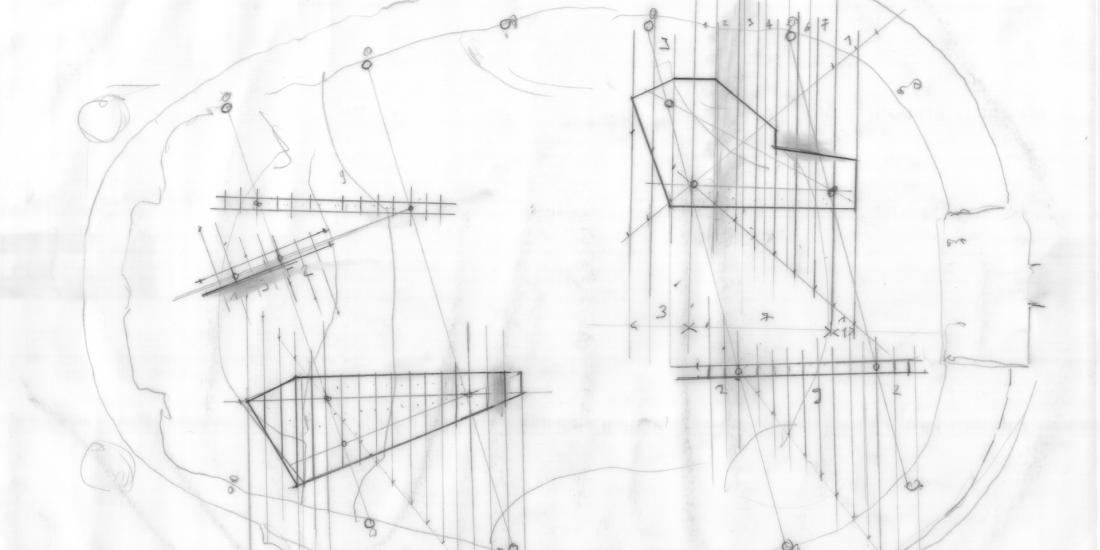

Paul: “Reflecting on music also made us look at our drawings differently. Gradually, our plans for Staging the Concert even started to resemble scores. For me, that was perhaps the best thing about this commission.”

Bartók in Space and Time by Robbrecht & Daem Architecten takes place on 20 September in the Henry Le Bœuf Hall. Alexander Vantournhout (13 February) and Baloji (30 June) are designing the next instalments of the Staging the Concert series.