Eline Hadermann wrote this article for La Monnaie, in the context of the series Mahler: the symphonies (Belgian National Orchestra, La Monnaie and Bozar).

Sketches and fairytales

Although Mahler never published an opera of his own, he had an affinity for opera composition. In 1886, for example, 65 years after the death of Carl Maria von Weber, Weber’s grandson asked Mahler to finish his last opera project, Die drei Pintos. After some hesitation, Mahler accepted the challenge and not only orchestrated the seven bequeathed musical sketches, but also incorporated other works by the composer and personally wrote an additional ten new scenes. It was a process that gradually gave Mahler the confidence to follow his own sense of style. “As reluctant as I was at first, I became equally as bold in the course of the work (…) and ultimately simply composed in my own way and became increasingly more ‘Mahler-esque’,” he told Natalie Bauer-Lechner.

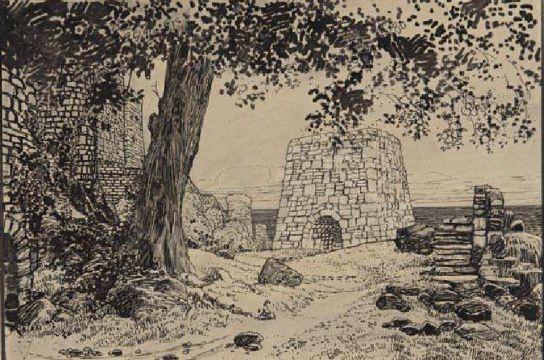

He had not yet found that ‘Mahler-esque’ style in previous attempts at opera composition. During his last years at the conservatory, for instance, he had begun writing Die Argonauten, only to destroy all the sketches, and Rübezahl, a fairytale opera about a mountain spirit from German folklore. Mahler’s libretto for the latter opera has survived and various letters attest to the fact that, over the course of ten years, he occasionally returned to his sketches, but never completed the project.

Inspired by German folk tales, he did, however, complete Das klagende Lied (1878-1880), a composition for a choir, six solo voices, and a symphony orchestra based on a fairytale in which two brother knights vie for the hand of a queen. With fratricide, a magical horn, and a major revelation during the last act, this Märchenspiel has a dramatic development that draws heavily on the opera genre. Incidentally, as a recent graduate, Mahler tried to launch his career as a composer with this cantata, submitting it in 1880 as an entry for the Vienna Beethoven Prize. But the members of the jury expressed reservations. Mahler’s first major opus was not considered because of the “Wagnerian sound that enveloped the fairytale in thick pathos”.

Under Wagner's spell

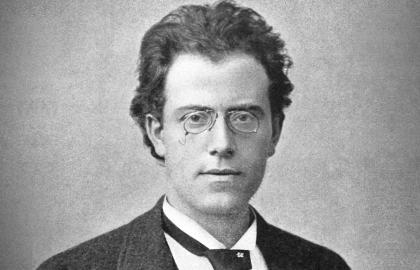

It is not surprising that Wagner’s harmonic innovations filtered through Mahler’s earliest compositions. Like so many others, the young Gustav was not unaffected by the magnetic allure of the New German School. His pilgrimage to Bayreuth in 1883 left a lasting impression and fuelled a desire to have the opportunity to conduct Wagner’s musical dramas. He was ultimately given that opportunity in the German-language theatre in Prague, where his conducting career got off to a flying start. From 1888 on, Mahler established himself as a conductor in the opera houses of Leipzig, Budapest, and Hamburg, where he specialised not only in Wagner, but also Mozart, and appropriated a major part of the standard repertoire.

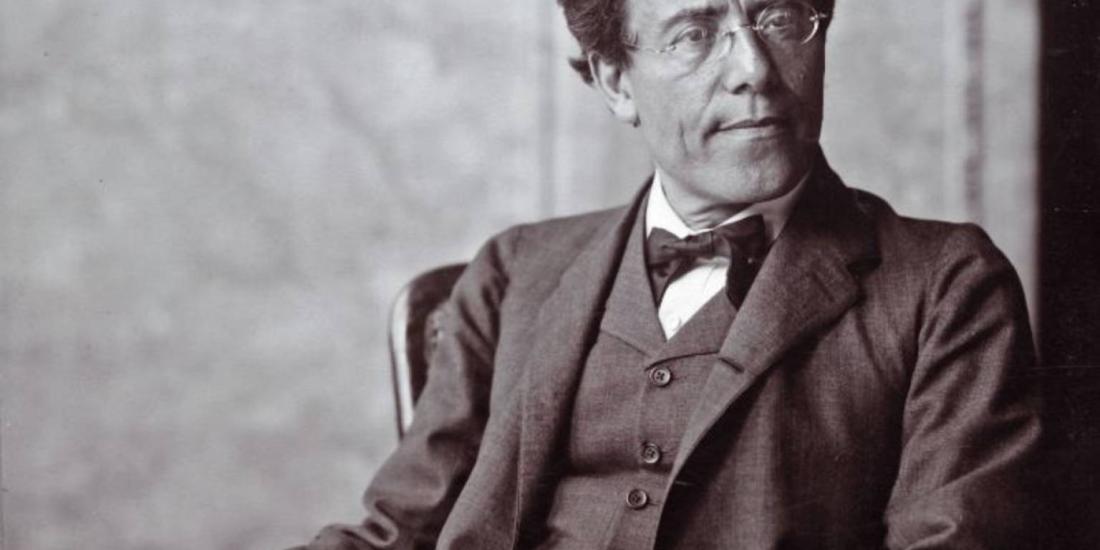

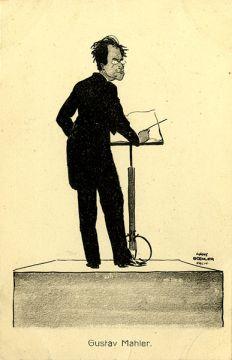

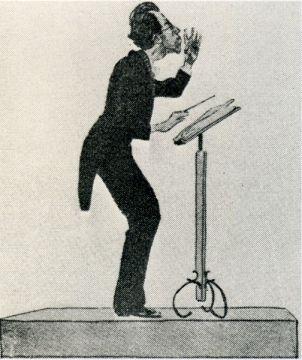

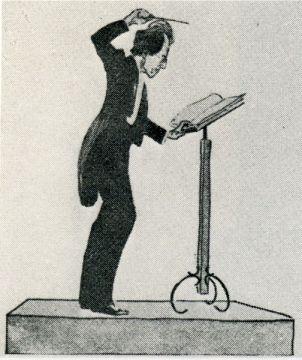

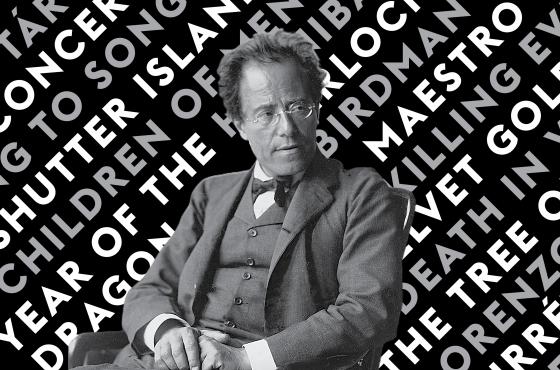

An important new step in his career followed in 1897, when he was first appointed Kapellmeister of the Vienna Court Opera, before taking over the direction of this prestigious house a few months later. ‘Mahler the conductor’ made his mark here, not only due to his lively and energetic conducting style, but also the numerous innovations he introduced. His musical interpretations were driven by the need to put an end to what in his eyes were meaningless traditions. His dynamic tempos made him infamous among quite a few music critics, and when conducting Wagner’s musical dramas, he only used the original scores without the cuts that were in vogue at the time.

His innovations extended beyond the strictly musical. Twenty years earlier, Wagner had wanted to create an entirely new, almost edifying opera experience. To distract the audience as little as possible from the drama on stage, he made the orchestra invisible and dimmed the lights in the theatre for his Festspielhaus. It was Mahler who introduced such innovations, which continue to be the norm in opera theatres to this very day, in Vienna. He, too, darkened the theatre and orchestra pit, issued a ban on seating latecomers until after the next intermission, and put an end to claques – the tradition in which a group of audience members are paid to applaud.

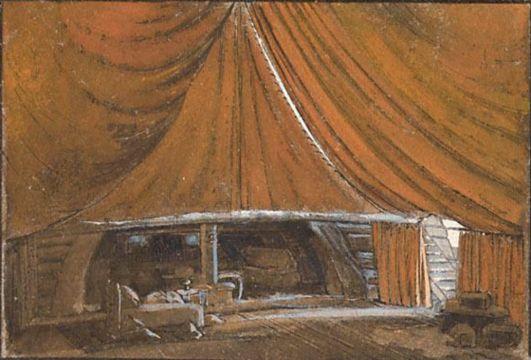

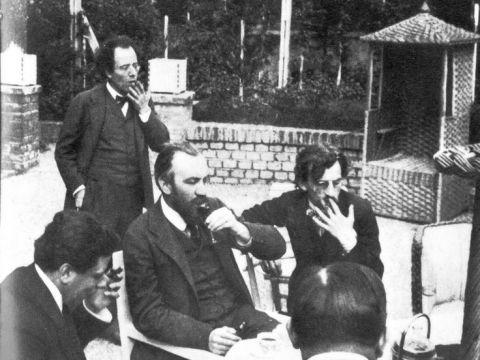

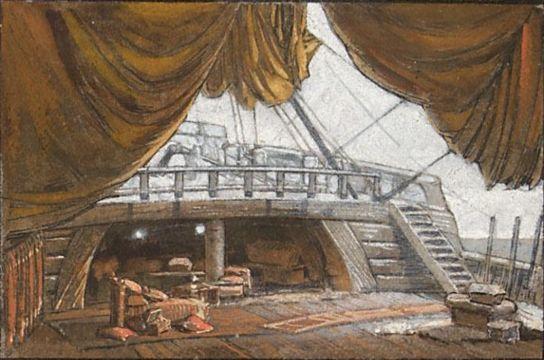

Mahler also had a considerable impact on what took place on stage. Once again following Wagner’s example, he was driven to stage an opera as an integral work of art. He completely disregarded old acting and directing practices – “tradition is sloppiness” was declared during rehearsals on more than one occasion. Bruno Walter, conductor, contemporary, and confidant, claimed that ‘Mahler’s dramatic talent’ was as great as his musical skills. “His importance as an opera conductor rested on this. Equally at home on stage as in the music, he could bring both the scenes performed and the musical performance to life with his passion and spirit, and direct his performers towards the fulfilment of both the theatrical and musical demands of a piece.” When Mahler became acquainted with the painter and designer Alfred Roller (1864-1935) in 1903, he found the perfect partner to translate his artistic vision to the stage. Roller’s revolutionary, colourful designs took a step back from tradition and headed straight for the essence of the drama. Their Viennese production of Tristan und Isolde (1903) sent a shockwave through the opera world, due in part to the scenography and innovative use of lighting.

Kulissenschmutz

Neither Mahler’s early explorations nor his passion as an interpreter of the genre ultimately resulted in the creation of his own opera composition. And that is perplexing, as his oeuvre betrays a considerable affinity for the human voice and the literature.

From his Symphony No. 2, in which both vocal soloists and a large choir can be heard for the first time, Mahler experimented extensively with the vocal element within the symphonic form. According to Mahler, the idea of having a large choir as the finale emerged from an ‘aha moment’ at the funeral of Hans von Bülow, when he was “struck like lightning” by the Auferstehn Hymn by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, after which he claims that “everything was revealed to me clear and plain” and he knew how the last part should sound – and above all, which “decisive words” could be used for his symphony. And that was not a one-off event. Although he opposed interpretations of his symphonic work that were overly semantic and often revoked his own past interpretations, various letters and notes reveal that words, poetry, and philosophical questions were often sources of inspiration. In a letter to the German writer Arthur Seidl, he even wrote, “Whenever I plan a large musical structure, I always come to a point where I have to resort to ‘the word’ as a vehicle for my musical idea.”

During the working year, there was no time to develop these large musical structures. Mahler divided his professional activities so that he could focus on his directing and conducting career during the season and, in the summer, could retreat to Austrian ‘composing houses’ surrounded by nature. The two musical worlds were not only separated spatially, but for Mahler, were also of a fundamentally different order. He was convinced of an “intersection that permanently divides the two divergent paths of symphonic and dramatic music.” Anecdotes such as those from his friend Josef Bohuslaw Förster, who found him at the piano following an opera performance, enjoying the purity of Bach’s music to “get clean” from all the Kulissenschmutz (theatre dirt), might even suggest that, as enthusiastically as ‘conductor Mahler’ expressed himself about the opera scores on his desk, ‘composer Mahler’ was rather ambiguous about the genre. Such a witticism, however, cannot compete with a lifelong commitment to the theatre, and, according to musicologist Kurt Blaukopf, even ‘composer Mahler’ took from that very same “Kulissenschmutz” all the “technical means of expression that could be of use to him as a symphonist”.

Searching and with restless steps, the opera conductor and composer in Mahler each followed his own path, without ever losing sight of the other – a dichotomy which both opera houses and symphony orchestras continue to reap the benefits of.

Eline Hadermann is a literary scholar and writer. Passionate about opera since childhood, the art form took centre stage in her studies of Dutch and English Language and Literature and Comparative Literature. Having previously written for the Editorial and Dramaturgy Department of Nationale Opera & Ballet Amsterdam, she has been working as a Content Writer for La Monnaie since 2023.