No birth without a name

The term ‘surrealism’ was first used in 1917, in a preface by the French writer Guillaume Apollinaire. He used it to describe an art that transcends reality, writing: ‘When man wanted to imitate walking, he invented the wheel, which does not look like a leg. Without knowing it, he was a Surrealist.’ Breton borrowed the name in 1924. The Surrealists were artists who abandoned logic in pursuit of a new reality. They expressed irrational ideas through dream images, unexpected combinations or distorted perspectives.

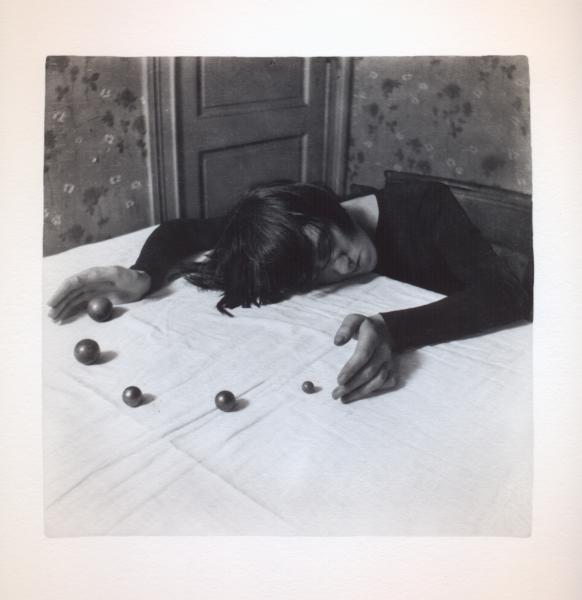

Paul Nougé, The Juggler, from the series Subversion of images, 1929-1930.

The first words: dada

The rejection of rationality did not come out of nowhere. In fact, the rational drive for progress was seen as a cause of the First World War. The Dada movement, which originated in Switzerland, took an oppositional stance as early as 1916 by denouncing the art of the day. The Surrealists and Dadaists had similar ideas, namely that art should have an impact on society and that art and poetry were inextricably linked. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical texts were a second and important source of inspiration. His theories opened up new ways of looking at reality and explored the subconscious: the inner truth over the general. At the same time, under Breton’s stimulus, communist ideals infiltrated the Surrealist groups. Anti-capitalist sentiment reached new heights when the boom years of the Roaring Twenties collapsed like a house of cards in 1929.

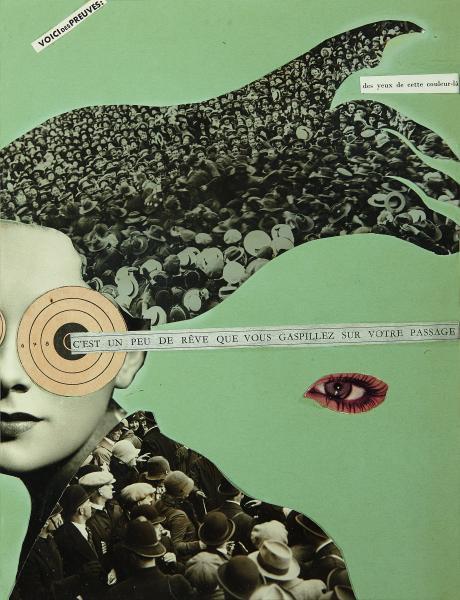

Max Servais, C'est un peu de rêve…, c. 1934.

Brussels as a playground

The Belgian Surrealists were amongst the first to step onto the world stage, appearing not long after the publication of The Surrealist Manifesto (1924) in Paris. In Belgium, pamphlets were printed on brightly coloured paper, signed by ‘Correspondance’ and with a Brussels address. The man behind this action was the poet Paul Nougé, who would come to play a leading role as the inspirator (tête pensante) of Belgian Surrealism. Camille Goemans and Marcel Lecomte co-wrote pamphlets and participated in the first Surrealist salons, together with René Magritte and composer Edouard-Léon-Théodore Mesens. The movement was the catalyst for numerous meetings and publications. Influenced by Giorgio de Chirico , Magritte drastically changed his painting style in 1925 and abandoned Cubism and Futurism. Belgian Surrealism had taken its first steps.

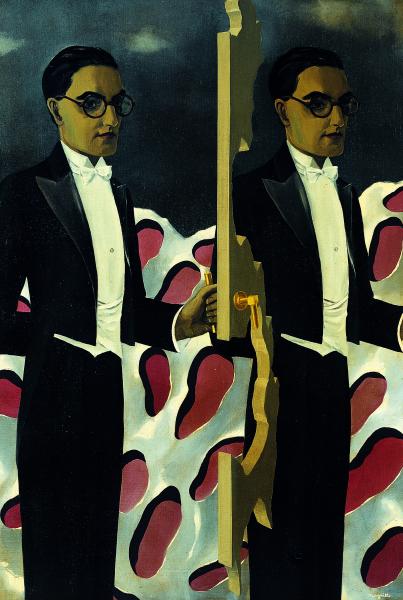

René Magritte, Portrait of Paul Nougé, 1927.

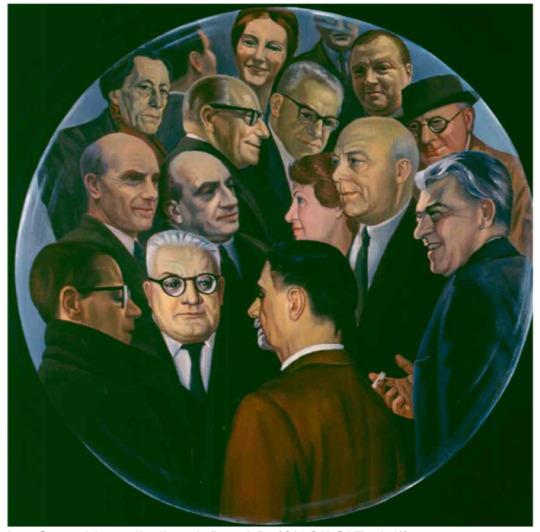

Magritte’s friendship book

Individuals came and went in the Brussels-based Surrealist group, which became increasingly ‘vocal’ in the 1920s. Members disrupted French avant-garde performances and criticized the French movement centred on Breton. 1927 was a pivotal year for the Surrealists. Magritte had his first solo exhibition in Brussels, which introduced his Surrealist art to a much wider audience. And despite the sensitive relations with French artists, he moved to Paris. Magritte painted feverishly in the French capital for three years. He created his first word paintings in the city, visited the Salons and befriended Dalí. After disagreements with Breton, he finally returned to Belgium where he continued to play a leading role in the Belgian art world. He exhibited his paintings in the international exhibition Minotaure at the Centre for Fine Arts in 1934, alongside works by a growing number of Surrealists. A new Surrealist group called Rupture was established in Hainaut that same year. Belgian Surrealism went on to enjoy a long and healthy life: it thrived for sixty years and spanned three generations.

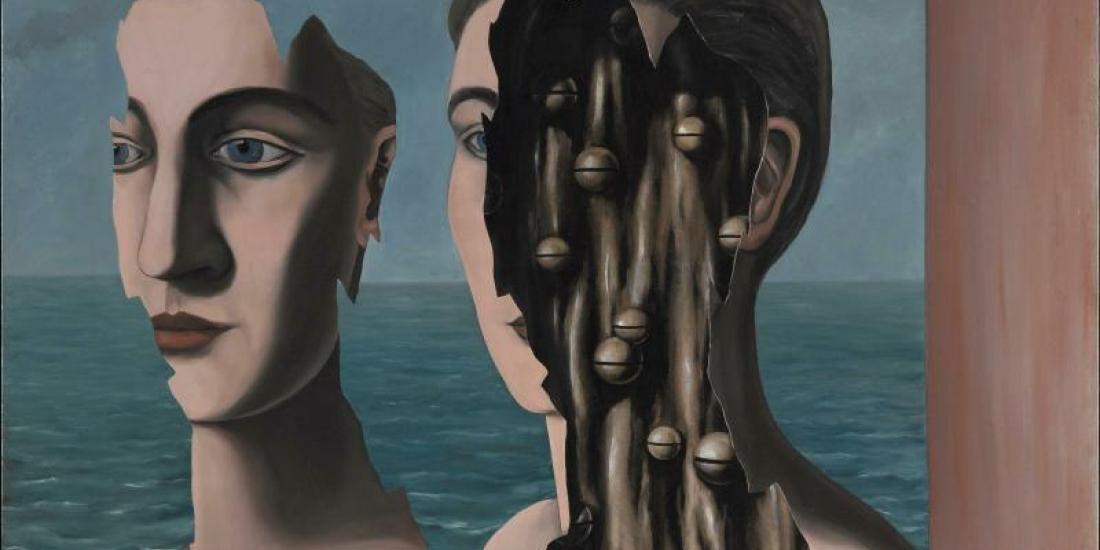

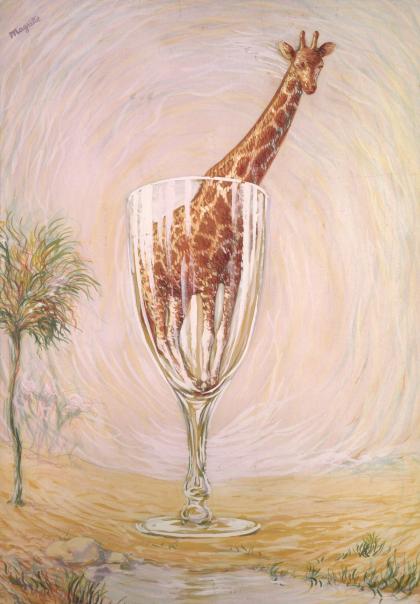

Jane Graverol, The Drop of Water, 1964.

Surrealism also provided a platform for many women artists. In our next blog post, we’ll be delving into the life and work of female Surrealists such as Rachel Baes and Jane Graverol.