What motivated the decision to create this festival?

It was mainly the current crisis in Beirut and the extreme difficulties experienced by Lebanese artists and civil society. The explosion on 4 August 2020 in Beirut’s Port, due to the haphazard storage of ammonium nitrate for many years, created new awareness of the situation. The catastrophic damage to the city brought a surge of solidarity from a very dignified Lebanese society. The festival’s event calendar also focuses on solidarity: Lebanese artists and writers are given free rein to speak about the country’s situation.

How is it possible that the Lebanese ruling class allowed the situation to deteriorate to such an extent?

It is a bankrupt system. The political elites of the various ethnic and religious factions have shared power based on a very fragile equilibrium. This state of fragmentation has lasted for decades. It was not easy to recover from a civil war that lasted 15 years. In addition to that, Lebanon has been exposed to multiple external forces due to its geographical situation. When you look at the state of Lebanon today, left to fend for itself, we felt it was necessary to give Beirut artists and writers the opportunity to show and tell us what they have to say. We therefore wanted to create a 72-hour space for Lebanon only. Of course, we would have liked to do more. It is nonetheless our way of showing solidarity with Lebanese society, with its intellectuals and its artistic and literary scene. Many rehearsal spaces, studios and cultural sites were destroyed by the explosion that hit areas close to the port. Areas that resisted the blast also had to be closed for cleaning and restoration. On top of that, artists have seen their mobility reduced due to COVID. Populations in Middle East countries have found it much more difficult to get vaccinated – with European Union-approved vaccines – than people from European countries. All of this has considerably hampered artistic activities in the past two years.

The festival opens with Told by my mother, on 12 November at 7:00 pm. What are the origins of this moving performance choreographed by Ali Chahrour?

In October 2019, the Bozar public was able to discover Ali with his performance May he rise and smell the fragrance. He had already been working on this current project at the time of Lebanon’s popular uprisings, prior to the pandemic and the Beirut Port blast. He recently went back to it, brought his team together and gave a major role to mothers. They tell their stories while dancing and singing to a backdrop of traditional Arab songs, which have been handed down orally through families. The work is based on the story of his aunt Fatima who saw her son Ali leave for Syria, never to return. A mother’s grieving for her lost son is put into perspective by the story of Laila, another mother, one of Ali’s relatives and not a professional artist, whose son did not leave and is still alive. The performance celebrates mothers – their struggles, their resistance, their bodies, their blood – and is enhanced by the magnificent voice of Syrian singer Hala Omran. At the core of Ali’s performance are ritual songs, which are part of the Arab heritage, and are chanted at times of joy or grieving. The contrasting fates of two mothers who sing and dance on stage is a celebration of all Lebanese women and mothers, of their strife and resilience.

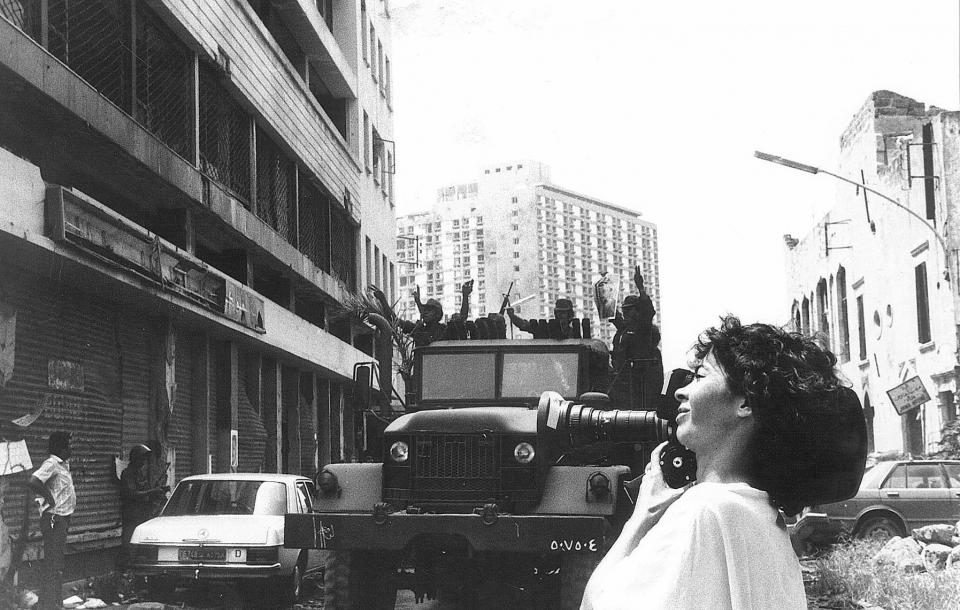

The second evening, on 13 November, opens with Letter from Beirut by Jocelyne Saab. Why did you choose to screen this 1978 documentary?

Jocelyne Saab was a major Lebanese filmmaker. In her film, she writes to Etel Adnan, a highly eminent Lebanese visual artist and poet, now aged 95. Both women were very influential in the Lebanese cultural landscape. Jocelyne Saab crosses Beirut by bus and asks people questions. The issues she addresses and how they are treated at the time, could very well be the same nowadays. As the past often explains the present, going back in time can help us to project into possible futures. That is why we begin by showing this moving film whose surprising present-day relevance provides food for thought. Its universal dimension is very striking; what happens in Beirut could happen or has already happened in other cities, in other parts of the world. It is also important to show the links between the first generation of artists such as Etel Adnan and Jocelyn Saab, who shaped the modern era well beyond its Western facets. The contemporary artists from the Arab world who we celebrate today are also witnesses and heirs to what they achieved, to works by artists and intellectuals who preceded them.

The evening will also see a number of discussions…

Yes, the screening will be followed by what promises to be a passionate political debate between Elias Khoury, a great Beirut writer, and political scientist Ziad Majed. It will be moderated by journalist Safia Kessas. Later, a literary discussion titled Writing the self as a language for others, will be moderated by Leila Shahid, honorary president of the Mahmoud Darwich Chair. It will bring together two young Lebanese writers, one who writes in French and the other in Arabic. Dima Abdallah and Katia Al Tawil will look at literature through the language that conveys it and makes it meaningful. The next discussion will evoke Beirut through its cuisine. Farouk Mardam, known for his great talent as a publisher at Actes Sud, has written a number of works on the subject. Ziryab: Authentic Arab Cuisine, a collection of his culinary articles, was published in magazine Qantara, under the pseudonym Ziryâb. He will be talking to Ryoko Sekiguchi whose book of recipes, 961 hours in Beirut (and 321 dishes that accompany them), published by P.O.L., chronicles the Lebanese capital where she lived. We will end the evening with some slam. Dima Matta, a slam poet from Beirut, and Samira Saleh, a poet living in Belgium, will present excerpts from their work. To end this day as it began, I suggested reading a portion from a conversation between Jocelyne Saab and Etel Adnan, which helps to understand present-day Beirut. This reading will be all the more meaningful coming from two writers from the young generation.

The festival ends on 15 November with the screening of Skies of Lebanon, a film by Chloé Mazlo. Does it juxtapose the vision of an idyllic and European-centred Beirut with the harsh reality of its history?

Yes, this contrast is the theme of the first feature film by Franco-Lebanese director Chloé Mazlo. In the 1950’s, the main character, Alice, leaves Switzerland for Lebanon, a sunny and exuberant country troubled by the advent of civil war. The film questions the fantastic, idealised and romantic representation of Lebanon, a stereotyped image which distorts reality, held for a long time in Europe. We must stop calling Lebanon “Little Switzerland” and Beirut “Little Geneva”. These are convenient images for those who wish to reduce the cities to tourist destinations. They prevent us from seeing Beirut’s real current situation, and from seeking solutions to the problems that the city and the country have been facing for many years.