Telling the story of the Harlem Fantasy Ball Part II of 1982, one of the tasks of the exhibition The Harlem Fantasy ‘82: Origins of the Royal House of LaBeija, is an exercise in embracing plurality. Embracing the plural historical, political, personal, social and relational dynamics, perspectives and memories of all those involved, and the context that surrounded them.

It is a task in honoring the memory of the producers of the ball, Pepper Lolita Labeija and Ms Dorian Corey, and their contribution not only to the Ballroom scene and community, but how the resultant reverberations of their contributions have vibrated throughout art and culture globally up until today.

To appreciate the cultural significance of this moment in history we, naturally, have to go b(l)ack. B(l)ack to the avant garde vision that the Harlem Fantasy Ball Part II represented, and the people who championed that vision.

“The Harlem Fantasy Ball Part 2 , August 1982 held at "The Crystal Ballroom" on 125th in Harlem NYC USA, was solely produced by Pepper Lolita Labeija, the Empress of the Royal House of LaBeija, along with Ms Dorian Corey. This was their event. It was a Signature Ball.”

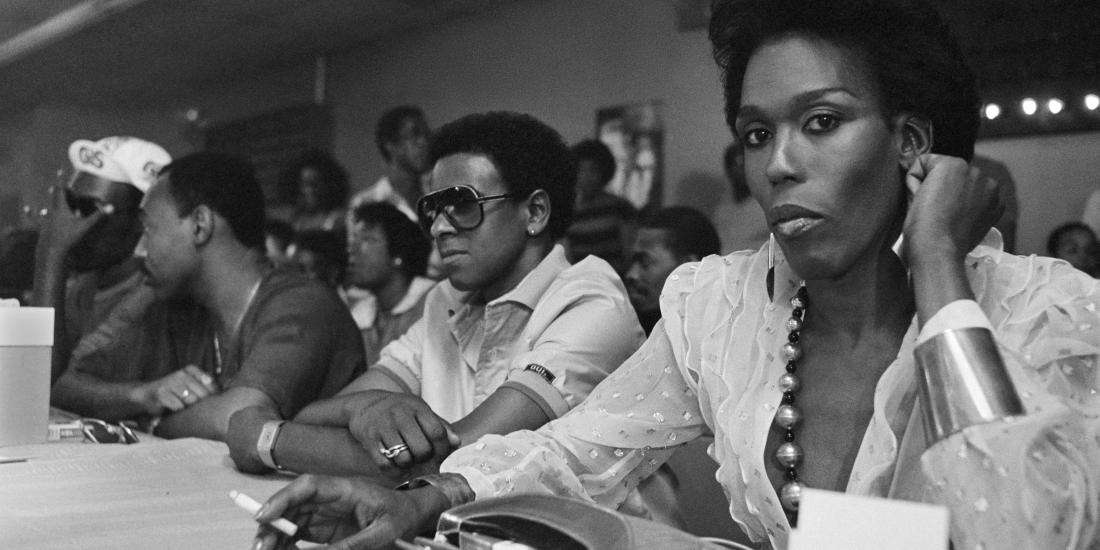

What you see in the exhibited images of the photographer Nick Kuskin throughout the exhibition is a snapshot of the energy and vitality that thrummed through the Ballroom community of 1982. Nick was invited as part of a documentary team to capture the historic night at the invitation of Simone di Bagno and Michele Capozzi, the producers of the film TV Transvestite that is the earliest known film documentation of a ball, also included in the exhibition.

Di Bagno and Capozzi themselves were invited by the ball producers Pepper Lolita LaBeija and Ms Dorian Corey. This is to say that, it was the ambition of LaBeija and Corey to facilitate a context in which Ballroom would be able to burst through the glass ceiling of black, queer representation of 1980’s North American culture and enter the mainstream. An achievement that would not only be fitting of the creative and cultural prowess of Ballroom, but also facilitate the material security of the people who constituted the Ballroom scene.

Simply put: black & brown, queer & trans folks; many of whom were or would be affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic whether directly or indirectly; many of whom did or would experience economic instability under the ravages of Reaganomics[2].

"Back then it was a barter system. Ballroom was about a barter system. A lot of gay, black men were living in SRO’s…the SRO was a “single room occupancy” and they shared the kitchen. But the femme queens, as we used to call them then, they’re now known as [transgender women], they would stay with you so they could actually transition. And that refrigerator you shared with the whole house is where they kept their hormones. And back then what it was, was: if I could go out and get a job I could get a room, and then you would stay with me so you could transition. And then you probably did sex work so we could eat. And it was just a barter system[3]."

Curatorially, the exhibition was, fittingly, a collaborative effort. Myself [Kopano Maroga], Nick Kuskin (as the photographer of the main body of the exhibition), Kevin UltraOmni Burrus (as the resident historian of Ballroom culture writ large), Jeffrey Bryant (as the current Overall Overseer of the Royal House of LaBeija) and Elena Ndidi Akilo (as the coordinator of the exhibition and the Afropolitan festival which served as the context for the presentation of the exhibition) worked together to ensure that the exhibition had a balance of breath to allow the artistic materials of the exhibition to speak for themselves, while ensuring there was enough historical and socio-political context to allow visitors of the exhibition the possibility to dive into the plural waters that this exhibition opens up.

There was much deliberation, conversation, robust debate, space for disagreement while knowing that our collective goal remained the same: doing justice to the story of The Harlem Fantasy Ball Part II, to Ballroom, to the people involved who could no longer be with us and, perhaps above all, to celebrate the memory of those both past and present and proposing a way forward for those in the Ballroom community of today.

“I felt, walking in, that I was walking into an avant-garde space. So I wanted to capture that for history.”

With the present day ubiquity of Ballroom culture in mainstream (arguably Western) media, whether in the forms of the Netflix drama Pose, HBO reality show Legendary, or the most recent album of Beyoncé Renaissance, I believe it is safe to say that the ambitions of Pepper Lolita LaBeija and Ms Dorian Corey to catapult Ballroom into the mainstream have been well achieved (and then some!).

However, it is paramount that we as cultural workers and cultural consumers remain vigilant against the misappropriation of Ballroom, and ensure that those who architected and continue to push its avant-garde agenda remain the central beneficiaries of this mainstream appeal. It has been well documented that documentaries like, Paris is Burning, have been prime examples of the expropriative vulnerabilities the Ballroom communities faces[4].

It is simply not enough to consume the culture knowing the inequalities the people at its heart: black people, people of colour, queer people and trans people, face. We must champion, celebrate, remunerate and protect those who contributed and contribute so much to contemporary culture.

[1] "There are Blacks in the Future": Alisha B. Wormsley, 2017.

[2] Reaganomics refers to a series of economic policies instituted in the 1980’s under the then president of the USA, Ronald Reagan. These policies aggressively favoured extreme “free market” economic principles over social welfare.