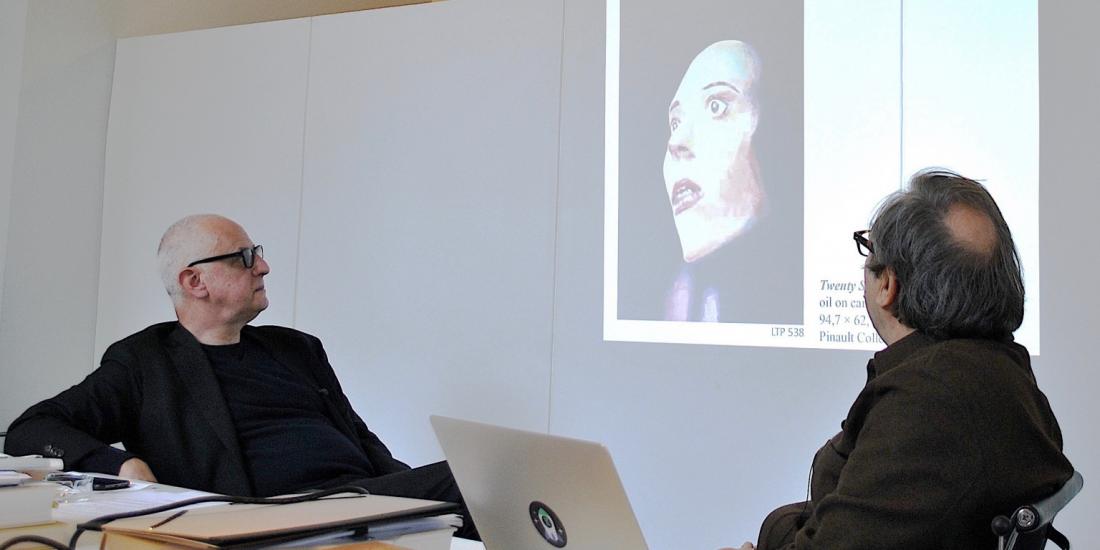

Luc Steels and his team at Studio Stelluti have analysed all the paintings that were on show during Tuymans’ prestigious 2019 La Pelle exhibition at Venice’s Palazzo Grassi. They used several AI techniques such as pattern recognition and computer vision, the semantic web, natural language processing and machine learning.

‘In my opinion AI is in no position today to even approach the complexity of interpretation of art. Not yet at least.

But I don’t think it will happen in my lifetime.’

The findings should eventually result in a collection of AI tools, called FLOW, that can support Tuymans and other artists in their visual research or artistic decisions. Can AI become for the 21st century artist what the camera obscura was for Vermeer in the 17th century? The following are excerpts from a working session between artist and scientist during the process.

Can AI understand art?

Luc Steels: In my opinion AI is in no position today to even approach the complexity of interpretation of art. Not yet at least. But I don’t think it will happen in my lifetime.

Luc Tuymans: Some people claim it will.

LS: Some people claim it will, but there is an extreme hype at the moment. In the past there was a kind of underestimation; people thought it would lead to nothing. Now, we have a kind of overestimation. Many people think you buy AI, sprinkle it over your computer, and some miracle will happen. That is not going to happen. But it is fascinating, in the case of art in particular, to see what happens with algorithms that have been designed to recognise images. To see what happens when you put those in front of an image. That is the first stage.

‘Many people think you buy AI, sprinkle it over your computer, and some miracle will happen. That is not going to happen.’

LT: My idea was to figure out if AI is intelligent enough to not only recognise an image but also retrace the source. My work is based on a source, so is AI intelligent enough to anchor an image in its source? To see how far back the recognition goes. The most interesting part of the whole project is to delve into the inaccuracies of it. What could come out of the errors, creatively?

Does AI look at a painting like we do?

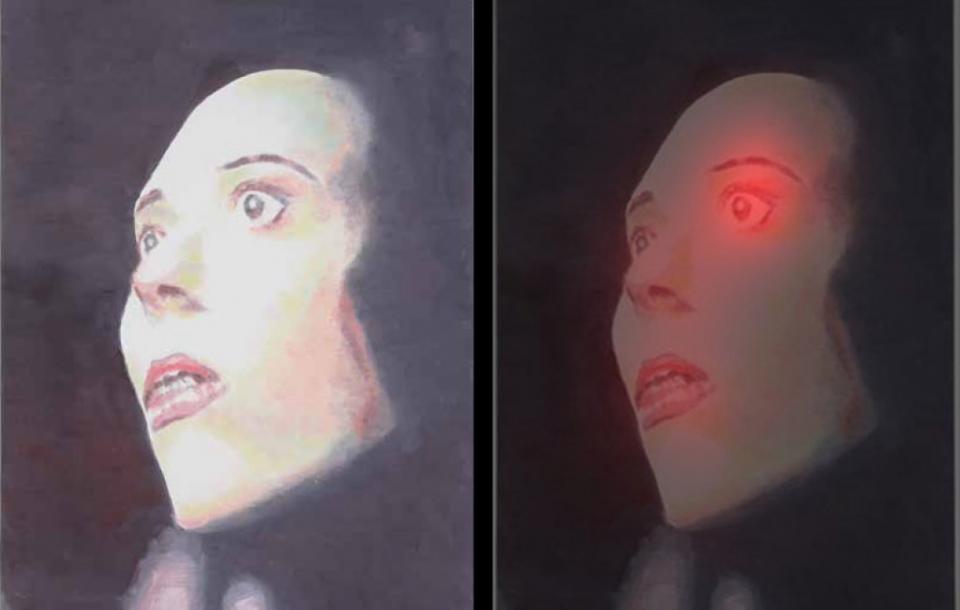

(They discuss the artwork Twenty Seventeen, 2017)

LS: We applied 5 different algorithms. The idea is to determine what part of the artwork draws your attention, what is the entry point for the viewer? We found that several algorithms were completely off, with no relationship to what a viewer would look at. There is only one that is reasonably decent.

LT: Yes. One that is spot on, the obvious one: the white of the eye. It is the most lit up part of the image, which makes the face almost come out of the frame. It’s the first thing you see.

LS: The algorithm is a collection of networks. A neural network that has been trained with data from people with eye tracking – to see where they look. But this was done using photographs, images of the world, not paintings. There are also some that point towards the lips.

LT: Which is also correct, but the main thing that lights up is the eye.

‘It is obvious to think that the eyes are the focal point in this painting. But in this image, it is more about the top of the nose and the forehead because there’s a sort of distortion in this image. But the algorithm goes for the most plausible thing, which is the eyes.’

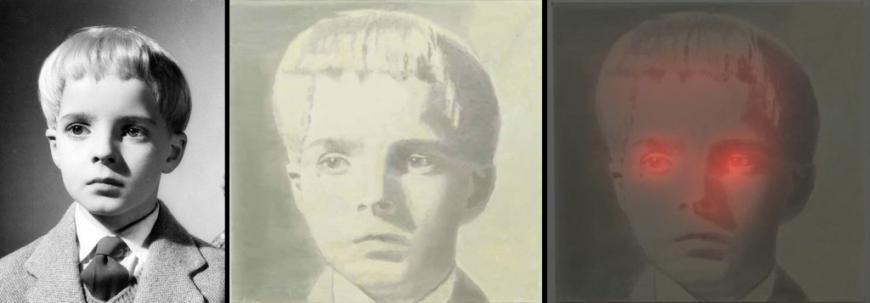

LS: Then we took another image, more complicated: The Valley from 2007.

LT: It is obvious to think that the eyes are the focal point in this painting. But in this image, it is more about the top of the nose and the forehead because there’s a sort of distortion in this image. And also the line between the light on the nose and the shadow next to it, it is an interruption in the image. But the algorithm goes for the most plausible thing, which is the eyes.

LS: There’s for example a little opening in the nose line. I suppose it is made on purpose.

LT: Yes, it is. It isolates even more the focal point zone we described before. It really targets it. There is an implausibility. Whenever you make a mistake, even though the viewers may not understand that mistake, but they will feel that something is not working. That’s how it settles in your memory. The brain will store it and refer to it.

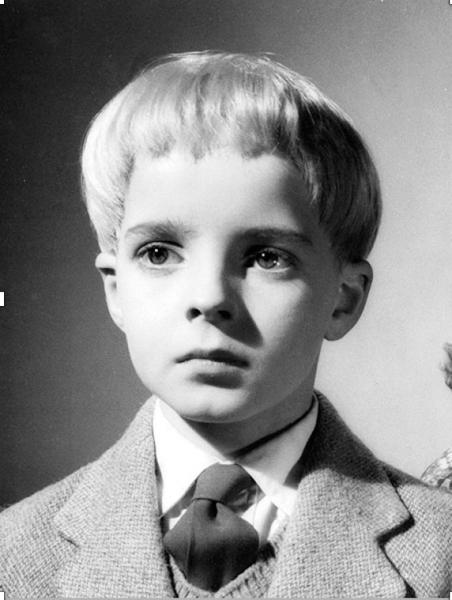

In the photograph, the source image for the painting, the eyes of the child are wide open. This kid could be innocent. If you look at the painting, you’ll see a difference in the eyes. This kid is like damaged goods. Which is not obvious when you see the kid as such. The kid in the picture is perfect; the kid in the painting is imperfect. By reworking the image, just by the manual aspect of painting it, you make changes, you make an interpretation - whether you want to or not.

The child’s face in the painting is also more elongated than the one in the photograph. As a painter you also project your physicality onto it. It has been discussed many times before, with the elongated figures of El Greco for example, and it is something that should be taken into account. It is uncontrollable.

Can AI find the original material a work of art is based on?

LT: Did the algorithms find the image on which the painting is based immediately?

LS: Well… with a little bit of help.

(They both laugh)

If you add the name of the work “The Valley”, just that single word, that changes things a lot, it’s a very important clue. If you just search by image, because you can also put an image into the search machine, the original photo doesn’t come up. There are so many images on the web that it overpowers the original. So, title and image have to come together to find a result.

« Il y a tellement d’images sur le web que l’original est comme noyé parmi les autres. Il faut donc utiliser à la fois l’image et le titre pour obtenir un résultat. »

How does the algorithm react once it leaves the comfort zone of the data it’s been trained on? Could a Zebra for instance trick an algorithm?

LS: We’ve been working with a new sort of algorithms called Segmentation Algorithms, trained on millions of data. These algorithms work on these data, work on images very similar to these data but once you go out of this comfort zone, even if you just shift a little bit the image, or you add just one pixel, you can ruin the results.

‘Once you leave its comfort zone, even if you just shift a little bit the image, or you just add one pixel, you can ruin the results.’

Luc Steels

Another possible mistake of the algorithms is when one element of the painting overtakes the attention of another. Let’s take the example of a painting where you have a person and a zebra in the same painting. Although the algorithm has been trained on facial recognition, it could easily be tricked if you show him an image of a zebra, because that image will be so strong for the algorithm that it forgets the person in the painting.

Could algorithms shine a new light on the curating process of an exhibition?

Could AI be the next curator?

Could it tell you which paintings you should hang next to each other in an exhibition, based on a colour scheme?

LS: We have also been playing around with colours. We take the pixels in the image and project them in the colour space to see the gradation. We can measure how extensive your colour use is. There is also a clustering algorithm to see which colours are mostly used in a painting. You can compare colour spaces of different paintings. Two works that hang next to each other in an exhibition for example. If you analyse the colour spaces the paintings are using, then you can start to group works together. There are many dimensions you can play with. For instance, to track the evolution of the way you use colour over time.

‘If you analyse the colour spaces the paintings are using, then you can start to group works together.’

LT: Which is possible to do, I think. In the first part of my catalogue raisonné the colours tend to be warmer. The second part is much cooler. That’s because I started to use polaroids, in 1995. The colours are immediately derived from the colours of polaroid pictures and they have an element of violet in them. And in the third part, the colour indigo becomes more important. So, the earth colours will refer to the first part, then you get these more artificial colours. The light also changes: from normal light to the light of the polaroids, which is reduced, and then finally you get to digital light. So that is something you can actually trace.

Colours are not pre-prepared, they grow organically during my painting process. Colours are mixed on the spot, tested next to the painting because there’s a difference between seeing colours flat on a table or vertical.

LS: That is something we could detect with an algorithm. A computer can see things that the human eye couldn’t see in terms of layers of colour.

Can an algorithm reconstruct the connections the artist made in his research for his artwork?

(They discuss Tuymans’ use of images of nazi architect Albert Speer and of the famous Villa Malaparte as it appears in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le mépris)

LS: The way your brain makes links between these references and inspirations, the connections between them, this can be reconstructed because these links can be found in the huge knowledge graphs that currently exist.

LT: I think that’s an interesting idea – to see what the patterns would be; the way the dots are connected. Because inevitably there are patterns, things that will recur, obsessions, fascinations, compulsive elements.

LS: That’s also the game you play with the titles, the contexts, the ordering of paintings in an exhibition. You put people inside these networks so that they make connections …

LT: But most of the time they don’t. (Laughs) But that could lead to interesting results if this order is decided by algorithms. To see if we end up with something different. Or something that is the same… but different. That will be interesting.

‘Most of the time, people don’t understand the network they are placed into when looking at a painting. But it could be interesting if this network was decided by algorithms instead of the artist himself.’

The results of these experiments will be discussed at BOZAR in Fall 2020 as part of the S+T+ARTS exhibition (Science+Technology+the Arts).

FLOW will be an available open source for the entire community of artists, curators and historians via the platform Penelope.

More information on this current research:

Steels, L. & B. Wahle (2020), "Perceiving the Focal Point of a Painting with AI: Case Studies on Works of Luc Tuymans", in Proceeding of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 2, 895-901, 2020, Valletta, Malta.