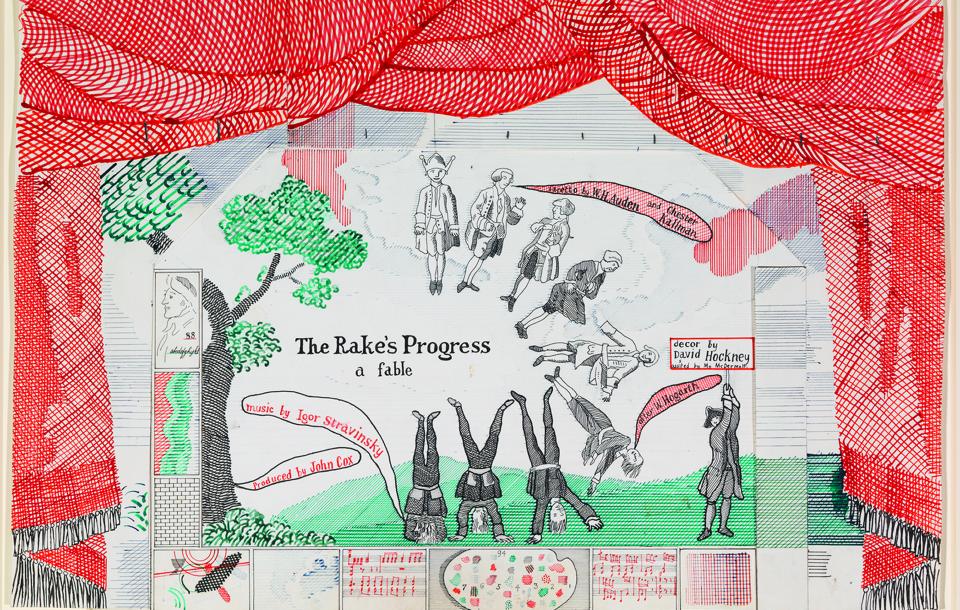

The Rake’s Progress (Stravinsky) – 1974

In 1974 Hockney received his first commission for an opera, and immediately one of great stature: The Rake's Progress (1951) by Igor Stravinsky, for the annual Glyndebourne Festival. The modern composer drew on a series of engravings by the 18th-century artist William Hogarth. It was the very first and also the only opera Stravinsky ever wrote. It premiered in 1975, but in 1992 you could admire Hockney's sets again in our Monnaie Theatre in Brussels. Like Stravinsky, Hockney was also inspired by Hogarth's engravings. He came up with a play of lines in muted colours for both the sets and the costumes: as if you were watching, and listening to, a large moving engraving.

Hogarth's series portrays 18th-century England in a satirical manner. Hockney based his work on the engravings for the eponymous A Rake's Progress (1961-63), the etchings of which can be admired in the exhibition. Hockney's early commercial success enabled him to make his first trip to the United States. Between 1961 and 1963 he portrayed his journey in this work, in which he, much like a contemporary Hogarth, recounted what it meant for him to arrive in New York as a young homosexual man.

Die Zauberflöte (Mozart) – 1978

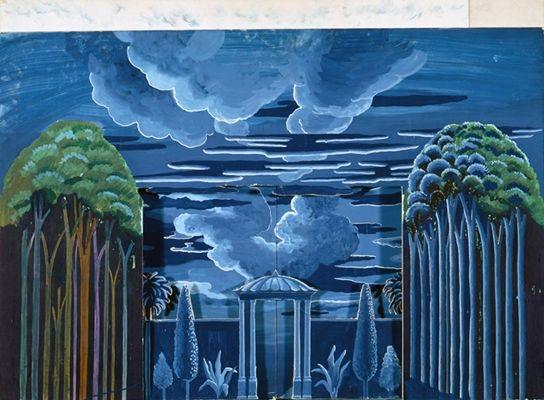

Hockney worked again for the Glyndebourne Festival a few years after The Rake's Progress premiered. He designed the sets and costumes for Mozart's Die Zauberflöte (1791). Whereas in The Rake he used Hogarth as his inspiration, now he drew on a number of 14th-century Italian paintings by Giotto and Uccello, among others, and the art of Ancient Egypt. The result was no fewer than 34 gigantic stage panels, in which iconic characters, such as The Queen of the Night, Tamino and the bird catcher Papageno were beautifully showcased.

“I wanted to do it plain, with flats moving in and out, as they did in Mozart’s time. I decided, especially in the first bit, that the music was crisp and clear, with a lot of colour and fun. It was only in the 19th century that The Flute was thought to be so ponderous. I thought I’d begin like an Italian painting, with everything in focus. So I painted the rocky landscape for the opening scene without any tricks of perspective, and took the dragon from the Uccello in the National Gallery.” – David Hockney

Tristan und Isolde (Wagner) – 1986

In 1986, Hockney was commissioned by the Los Angeles Music Center Opera to stage an opera of his favourite composer: Richard Wagner. He immediately jumped at the chance: "I don't just love Wagner, I'm addicted to his music. Moreover, Tristan und Isolde is a relatively static and uncommonly introverted drama. It takes place entirely outside. Staging nature seemed like an interesting challenge." Whereas in his early stage work, he used drawings, he now built mock-ups straight away, enveloped in the light and colours of California.

"The first thing we did was test out the light in the mock-ups. [...] And we kept listening to the music, nights on end. After all, we could only work at night because during the day, my studio could not be darkened." - David Hockney

The light became, as it were, a guideline for the emotion, something that Wagner already hinted at in his libretto. "Das Licht! Das Licht! O dieses Licht", sings Tristan in the second act, with which he curses daylight and longs for the twilight of the night.

Behind the wheel with Wagner

"I am one of those people who can hear colours and see sounds. In Los Angeles, I created the Wagner Drive. This is when I would race through the mountains in my convertible, which was equipped with 18 speakers because of my worsening hearing. Behind every corner, I met with a different light, while the music sounded different too. Wagner's music, which I love above all else, cries out to be experienced in a sensuous way like this. Everyone I have taken on this drive comes back a different person. And it is precisely those experiences that I want to convey on stage." - Hockney in Der Spiegel, 1997

In the 1990s, Hockney decided to buy a beach house at the foot of Las Floras Canyon in California. Not much later, his audiovisual masterpiece Wagner Drive was created, a route you can follow by car on the Pacific Coast Highway and in the mountains of Santa Monica. Hockney also made beautiful paintings of these impressive Californian landscapes. You'd like to get lost in them. And you can do so until 23 January in the double exhibition at Bozar.

Listen to our playlist!

The music team at Bozar put together a playlist to complement David Hockney's twin exhibition. Listen to it here.